History of Art students enjoyed the beauty of the ‘Pre-Raphaelite Sisters’ exhibition but wondered if the curators could have dug deeper into the way these influential women were portrayed

L6 History of Art students recently visited the National Portrait Gallery to see the Pre-Raphaelite Sisters exhibition . The show (which closed on 25th January) aimed to honour the contributions of the women – models, mistresses, muses and artists – who were so crucial to the emergence of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Students could not help but be impressed by the sensuousness and technical sophistication with which the 'sisters' were portrayed. Dasha liked the way Il Dolce far niente by William Holman Hunt, above, portrayed 'warmth and idleness'. 'I liked how direct, simple and beautiful it was,' she said. Elena's favourite was John Everett Millais's 'Death of Ophelia', below: 'The brightly coloured flowers floating on the surface of the water directly draw the viewer's eye to Ophelia’s beautiful, ornate dress and eerily lifeless face,' she wrote.

But the the portrayal of women also set the students thinking. Many commented on the way that the numerous different women who modeled for the group – which was initially known as the 'Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood' – all seemed to look the same in the paintings, each becoming a sort of idealized beauty with a prominent chin, full lips, and fiery red hair.

Questions also began to arise about the shortage of work by women in the exhibition. Why was there so little work by female artists – such as Christina Rossetti, Elizabeth Siddall and Jane Morris – who had been part of the Pre-Raphaelite scene? To be fair, as none of these were portraitists, it might have been difficult to include them in a National Portrait Gallery exhibition. Even so, Darcy was not alone in thinking that the paintings of the women who did make the cut – such as Marie Spartali Stillman and Evelyn De Morgan – were given too little prominence: ‘Due to their placement close to the end, I feel as they were overlooked, as often that's where the viewer's focus begins to fade’.

Darcy also believed that the curators should have dug deeper into both the biographies of the 'Sisters' and the way they were depicted: ‘I understand that there is probably not a lot of information or sources on these women for the curators to work with but I couldn't help but feel that the exhibition was a bit one-dimensional. The women, particularly those in the model section, were given a small biography followed by a vast number of portraits, in which they looked glamorous and beautiful, seemingly making that the focus of the exhibition, rather than their lives or influence. I believe they also missed an opportunity to explore the representation of these women within the paintings, particularly that of the ‘fallen woman’ and what that meant within their society.’

I believe they also missed an opportunity to explore the representation of these women in the paintings, particularly that of the ‘fallen woman’ and what that meant within their society.

Darcy

One especially valuable section of the exhibition focused on Fanny Eaton, who became a model for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, typically for biblical scenes such as Simeon Solomon’s ‘The Mother of Moses’, above. Eaton was a Jamaican-born woman who came to London as an infant - shortly after the abolition of slavery. The inclusion of paintings such as Joanna Boyce Wells profile portrait of her, below, made a refreshing contrast to other models in the exhibition because she retained her individuality in the paintings depicting her, while male artists like Rossetti tended to morph the other models into one singular idealized image of the feminine form. Sally commented: ‘When we think of Pre-Raphaelite women, the first vision that comes to mind is porcelain skin and flaming auburn hair. But Fanny Eaton's presence in Pre-Raphaelite art encouraged me to reconsider nineteenth-century perceptions of both race and beauty.'

Fanny Eaton's presence in Pre-Raphaelite art encouraged me to reconsider nineteenth-century perceptions of both race and beauty

Sally

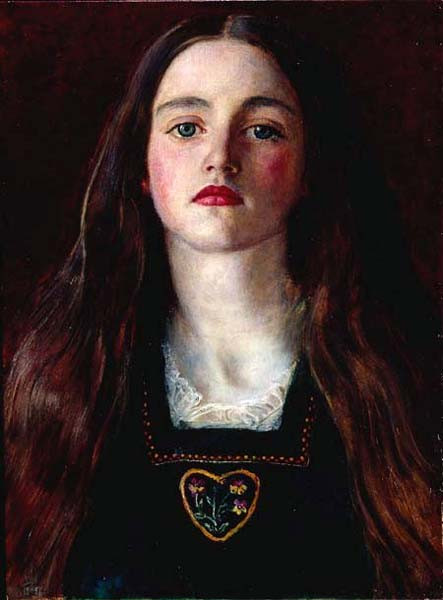

Another artwork which ran against the grain of typical Pre-Raphaelite portraits of women was Millais’ portrait of Sophie Gray, his sister-in-law, below. Ginevra explains: ‘Her gaze is described to be ‘direct and strikingly modern’ for a 19th century artwork, which is what I think makes this artwork so admirable, not only for Millais’ artistic technique but also the frank expression on Sophie’s face.’